Movable Interiors: Japanese Painted Screens

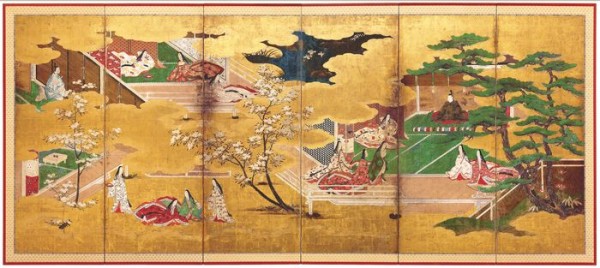

The Tale of Genji, early 17th century. Artist unknown. Pair of six-panel screens; ink, colors, and gold on paper. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Robert Allerton in honor of Mr. and Mrs. William McCormick Blair’s fiftieth wedding anniversary(1962.574-75)

Dating back to the prehistoric cave murals of Lascaux in France, the Ajanta frescoes in India, the Mexican muralists, to name a few, mankind has adorned even the humblest abodes with art.

In Japan, where traditional homes, palaces and castles were sparsely furnished, the artwork took on a functional aspect as well. Japanese screens which combined painting, ink, gold leaf, poetry, calligraphy and design could be moved around according to need. The concept of the screens, which were known as Byobu, and originated in China during the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) were first introduced to Japan around the 700s.

Exquisite examples of these painted screens are now on exhibit at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.Beyond Golden Clouds: Five Centuries of Japanese Screens, on through January 16, 2011. On view are forty-one rarely seen large scale folded screens from the 1500s to the present. From sublime landscapes, intricate scenes recreating the invasion of ‘Portugese Barbarians, delicate ink strokes of chinese calligraphy to bold contemporary each of these pieces are distinct works of art that could easily be incorporated into any present day interior.

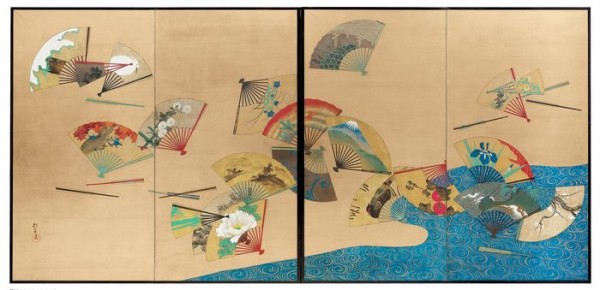

Fans and Stream, approx. 1820/28. By Sakai Hoitsu (approx. 1761-1828). Sliding doors (fusuma) mounted as a pair of two-panel screens; ink, color, gold, and silver on silk. Saint Louis Art Museum, Friends Fund(140:1987a,b)

The Asian Art Museum’s presentation of Beyond Golden Clouds will include an introduction to the fundamental compositions, materials, formats, and subjects of traditional folding screens, and a selection of self-guided thematic tours for visitors at every level of expertise and interest.

Thought to have been introduced from the Chinese mainland by the 700s, the folding screen provided Japanese artists with a large format that could transform an interior space and accommodate diverse forms of expression. Because screens are easily folded and moved, they can be interchanged according to season, occasion, mood, or decorative taste. The screens in Beyond Golden Cloudsencompass a range of styles that reveal the expansive visions of their artists—from grandeur, formality, and austerity to tranquility and contemplation.

By the Muromachi period (1392–1573), screens were being used for both Japanese-style paintings and the newly adopted Chinese tradition of ink painting. The earliest work in the exhibition is a pair of inkpainted landscape screens by Sesson Shukei (approx. 1490–after 1577; fig. 1). The golden age of the Japanese screen occurred in the Momoyama (1573–1615) and Edo (1615–1868) periods, during which painters used the format to display a range of subjects, styles, and compositions.

Beyond Golden Clouds also explores the diversity of creative expression in the early Edo period (1600s) through such works as Willow Bridge and Waterwheel by Hasegawa Soya (1590–1667) and Flowering Cherry and Autumn Maples with Poem Slips by Tosa Mitsuoki (1617–1691)—the latter by the director of the painting bureau at the imperial court. Other featured works from this era include a formal depiction of birds, flowers, and a pine tree on gold by Kano Koi (approx. 1569–1636), which may be associated with the renowned wall paintings at Nijo Castle in Kyoto; a pair of screens with scenes from The Tale of Genji, the renowned Japanese literary epic; and a superb set of screens bearing scenes of Portuguese missionaries and traders arriving at Nagasaki.

The 1700s and 1800s are represented by screens depicting both Japanese- and Chinese-inspired subjects. A set of twelve ink paintings mounted on a pair of gold screens by Obaku Zen priest Kakutei Joko (1721–1785) evinces Chinese tastes among Japan’s literati circles in the 1700s. An entirely different aesthetic is seen in paintings of fans and flowing water by Rinpa artist Sakai Hoitsu (1761–1828), who drew his artistic inspiration from a Japanese-style painting tradition. Originally executed on sliding-door panels, this painting was later remounted as a pair of two-panel screens. Other works on view include landscapes and calligraphy from both Japanese and Chinese literary sources.

In the twentieth century the Western-inspired establishment of annual juried art exhibitions encouraged Japanese painters to break away from traditional artistic conventions and create works using innovative compositions and colors. The strikingly dense and colorful pair of screens Blue Phoenix by Nihonga (modern Japanese-style painting) artist Omura Koyo (1891–1983) exemplifies this trend. Star Festival by Kayama Matazo (1927–2004), created for such an exhibition, is one of the best-known paintings of postwar Nihonga. Other artists in the late twentieth century moved even further away from their predecessors. The contemporary Mountain Lake Screen Tachi series by Okura Jiro (born 1942), though inspired by traditional folding screens, uses nontraditional materials and double hinges to function as a set of freestanding sculptural elements with limitless installation possibilities.’ Excerpted from the museum press release. Asian Art Museum

Star Festival, approx. 1968. Kayama Matazo (approx. 1927-2004). Six-panel screen; ink, color, gold, and silver on silk. Saint Louis Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Kayama Matazo, The Japan America Society of Saint Louis, and Dr. J. Peggy Adeboi(150:1987)

SukanyaRahman © Originally published in Art insider November 2010

Copy Right

All Rights Reserved ©Sukanya Rahman 2011

Categories