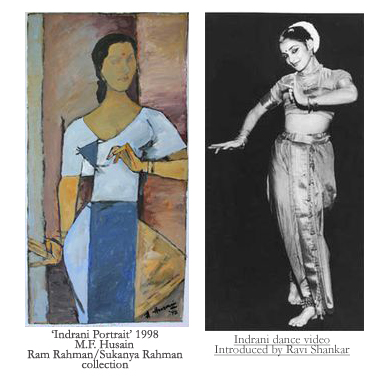

Indrani began to dance before she could walk. My mother made her stage debut at age five, performing the role of Maricha, the golden deer, in an episode of the Ramayana with her mother Ragini Devi and the dancer Gopinath.

Indrani began to dance before she could walk. My mother made her stage debut at age five, performing the role of Maricha, the golden deer, in an episode of the Ramayana with her mother Ragini Devi and the dancer Gopinath.

For centuries the tradition of classical dance in India was passed down from mother to daughter through generations of dedicated devadasis or temple dancers, and nurtured in the sanctums of the great Hindu temples. This ancient art traced its origins to the rituals of the sacred Vedas, and its ancestry to the celestial exponents of the dance, the apsaras or heavenly nymphs and to the gods themselves.

Oddly, this dance tradition—which had fallen into decline and disrepute during British colonial rule—was helped out of obscurity and placed on the world stage by a daring young woman from the American Midwest. Born Esther Luella Sherman, in Petoskey Michigan in 1893, Esther was convinced she had been a Hindu in a previous incarnation and her mission in life was to dedicate her life to Indian dance.

Esther scandalized her puritanical parents by performing exotic dances in small theatres and cabarets around Minneapolis. At the University of Minnesota she attached herself to a small community of expatriate Indians and immersed herself in their culture. She met and fell in love with Ramlal Bajpai, an Indian revolutionary and political refugee, and ran off with him to New York where they were married. Esther reinvented herself as a high-caste Kashmiri Brahmin. She took to wearing saris, and changed her name to Ragini Devi. She established a name as an accomplished dancer and author of the first book in English on Indian dance, Nritanjali published in 1930. That same summer she cast aside husband and career in New York and took off for India in search of Kathakali—a form of dance drama languishing in Kerala—undaunted by the fact that she was expecting a child. Ragini consulted a fortune-teller prior to her departure who predicted that this child would be a daughter, who was destined to become one of the most legendary dancers of her time. Ragini’s arrival in India coincided with the birth (September 19, 1930) of her daughter whom she had already named Indrani, Queen of Heaven, consort of Indra. She could picture the name in neon lights, blazing across marquees.

For the first eight years of her life Indrani was taken along by Ragini on her tours from the Himalayas to Cape Comorin and was swept up in her mother’s passion to dance. While Ragini was preoccupied breaking down barriers, determined to be the first woman to study the all-male Kathakali at the Kerala Kala Mandalam dance school, my mother was left to run wild. Her head crawled with lice, her fingers infected with scabies. Yet she claimed in later years that the happiest times of her childhood were those spent in Kerala.

Indrani had no education in the conventional sense, and a chaotic upbringing. A tour of Europe ended with her hastily departing Paris with Ragini, as police pounded on the front door demanding payment of unpaid bills. She was later smuggled across the Canadian border into America at age nine in a laundry bag. At the age of fifteen she married Habib Rahman, a dashing young Bengali-Muslim architect who was moonlighting as a dancer in Ragini’s troupe in New York. The couple returned to India during the communal riots of 1946 and I was born soon after, when my mother was just sixteen. But neither matrimony, motherhood or the birth of my brother Ram, nine years later, could stifle the magnificent obsession for dance Indrani had inherited from her mother. While I was thrust into the arms of a faithful Ayah, her life became one continuous dance-drama, both on stage and off, with a daily parade of gurus and dance masters wandering in and out of our flat.

Inspired by Shanta Rao, and guided by Ragini, she chose to study Bharata Natyam, the classical temple dance of South India. Ram Gopal advised her to have her basic training with U.S. Krishna Rao, who along with Shanta Rao was a disciple of the great guru Pandanallur Meenakshisundaram Pillai.

In 1952 Indrani became a household name when she was crowned Miss India, the country’s first beauty queen. I was both proud and embarrassed to see my mother’s beautiful face plastered on billboards, magazines and candy boxes. Indrani herself was determined to shake off the “stigma” of the title and establish a name as a serious classical dancer instead. Indrani emerged from her arduous training as the foremost disciple of the great guru, Pandanallur Chokalingam Pillai, and her career from that time on was one of spiraling success. A critic in the Tamil publication, Narada, noted “It was a surprise to all how a non-Tamil girl could have shown such abhinaya without long acquaintance with the language. We expect that Indrani will exhibit her art in many places in Tamil Nad…Our Bharata Natyam will shine in North India through her, more and more.”

Bharata Natyam was still a novelty to North Indian audiences. Post-Independence India was exploding with nationalistic fervor, its cultural future still waiting to take shape. Dance, music, the fine arts were in the process of rediscovery. Without abandoning Bharata Natyam, she returned to Kerala Kala Mandalam and studied the rare Mohini Attam, the feminine dance form of Kerala. After a decade of performing Bharata Natyam Indrani was restless to seek out other classical dance forms languishing in different parts of the country. When Indrani enquired about the Kuchipudi style from Andhra Pradesh she was told by a Tamilian in Madras, “Oh, it is all dead. There is nothing left to study. Why bother when Bharata Natyam is so beautiful?”

Yet she persevered. Kuchipudi was in decline in Andhra, but by no means dead. Fortunately, Korada Narasimha Rao, a disciple of one of the last great Kuchipudi gurus, Vedantam Acharyalu, was not only a brilliant performer, but inheritor of the tradition and a consummate authority on the dance dramas. Indrani added both Mohini Attam and Kuchipudi to her repertoire and helped bring those dance forms back to life.

For many years Ragini had been talking about a form of dance based on the rules of the Natya Shastra and described as the dance of “Odra Desa”, the ancient name for Orissa. Although she did not know its name she was certain the dance was still being performed by temple dancers in the Temple of Jagannath in Puri as part of the daily rituals. She believed this dance was one of the most perfect classical systems of dance still surviving in India. Ragini urged Indrani to go to Orissa to investigate these dances and report on whether this dance was classical or not. If it turned out to be what she thought it was, she should master it.

When Indrani first tried to find out more, she was once again told it was not worth the bother. Finally with help from the eminent Hungarian indologist and art critic, Dr. Charles Fabri, and his colleague Dr Mayadhar Mansingh, arrangements were made for Indrani to travel to Orissa where she become a disciple of Guru Deva Prasad Das.

On 19 February, 1958 I was watching from the wings when the curtain went up before a packed audience at the All India Fine Arts and Crafts Theatre. The air crackled with electricity as my mother, looking like a Konarak statue miraculously come to life, opened the performance with a Ganesh sloka, describing the beauty and attributes of the beloved elephant-headed god.

“Last night was an important milestone in the history of Indian dancing,” wrote Dr.Charles Fabri, “for this was the first time that a professional ballerina has presented true Orissi classical dances on the stage. He commented on “the seductive charm of rounded liquid movements marked by exquisite grace and sinuous flowing lines”, comparing Indrani’s dance to the charming dancers on the walls of the Rajarani temple of Bhuvaneshwar and the heavenly apsaras on the Sun temple at Konarak. “When the history of Indian classical dance is written,” Fabri later stated, “it will have to mention that it was Indrani Rahman who first brought together four great classical styles in one programme.”

At the time, however, my mother was often criticized for performing more than one style of dance. Yet it was this burning curiosity, the stretching of boundaries and daring to take risks, combined with diligent attention to detail, that made her unique and set her apart from her contemporaries. She was fastidious about every detail: lighting, original costumes, sound levels, length of performance, and punctuality which made Indian dance more accessible to audiences abroad

She became India’s ambassador of dance and performed for heads of state the world over, including Zhou En Lai, Mao Zedong, Ho Chi Minh, Dwight Eisenhower, Fidel Castro, Queen Elizabeth II, Richard Nixon, Khrushchev and John F. Kennedy. Emperor Haile Selase showered her with gold coins and commanded his daughter to remove her ornate silver belt and present it to her. My mother was honored with India’s most prestigious awards and was presented the keys to the city of New York by the mayor. But she was not satisfied to rest on her laurels. It was her mission to seek out, promote and encourage emerging artists and share the stage with them.

From 1968 on, her tours to the US became an annual affair. I began dancing and touring and learning from her in the early seventies. In 1979 we persuaded my grandmother to join us on stage in New York for a historic performance representing three generations of dancers. The audience, packed with many of the great names in American dance, rose to its feet and gave Ragini a thunderous ovation. She was ecstatic, completely taken by surprise. When the curtain came down she turned to me and asked excitedly, ‘Could I dance that again?’

Anna Kisselgoff of The New York Times called this performance, “One of the most brilliant and joyful presentations of Indian classical dance in New York…The hallmark of the family style is a blend of vivacity and refinement.”

In 1976 my mother became the first Indian dancer to join the dance faculty at the Juilliard School in New York where she taught for 15 years.

Without ceremony, around 1989, she stopped performing and devoted her last decade or so in New York to presenting performances by young dancers. Her goal was to continue educating and converting audiences to different forms of Indian classical dance. Until the last moments of her life she was busy organizing performances, rehearsing dancers and musicians, supervising stage lights and terrorizing all who would not rise to meet her standards. The energy she poured into producing these performances took their toll on her financially as well as physically. Indrani died in New York on February 5, 1999 at the age of 68.

© 2007 Sukanya Rahman dancer and visual artist, is the author of Dancing In The Family An Unconventional Memoir of Three Women published by HarperCollins. Some material for this article is drawn from Dancing in the Family, and appeared in slightly altered form in The Oberoi Group Magazine.

By Ragini Devi Dance Dialects of India

Originally published in Art Insider on 09/24/2009

Copy Right

All Rights Reserved ©Sukanya Rahman 2011

Categories