Mexican Nobel literature laureate Octavio Paz believed that “the Mexican people, after more than two centuries of experiments, have faith only in the Virgin of Guadalupe and the National Lottery.” Whatever the reason, anywhere you go in Mexico, whether it’s to grand cathedrals, grocery stores, neighborhood restaurants, even gas stations, the benign image of the saint of Guadalupe, encircled by a solar halo, is all pervasive.

Mexican Nobel literature laureate Octavio Paz believed that “the Mexican people, after more than two centuries of experiments, have faith only in the Virgin of Guadalupe and the National Lottery.” Whatever the reason, anywhere you go in Mexico, whether it’s to grand cathedrals, grocery stores, neighborhood restaurants, even gas stations, the benign image of the saint of Guadalupe, encircled by a solar halo, is all pervasive. The sleepy and somewhat rundown coastal village of Chicxulub Puerto in the Yucatan, famous mostly as a town where a giant asteroid of the same name crashed some 65 million years ago, is predominantly Mayan. Yet the central focus of every home, however humble, is a shrine to the patron saint of Mexico, most commonly decorated with kitschy plastic roses and colored electric light bulbs. But each year on December 12 Mexico explodes in even more fervent celebrations of the beloved saint’s feast day. Flags with images of the saint flutter on the front and backs of trucks. Teen age boys run around in T shirts sporting her image. Even the parking lot of a bus station was turned into a makeshift church for a service in her honor replete with an elaborate shrine, a priest in full regalia, musicians strumming guitars, the faithful seated in rows of plastic chairs and the local TV cameras in attendance.

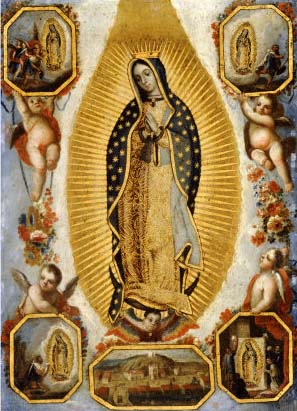

That the Mayans, whose culture and religion were decimated by the Spanish Conquistadors, fervently worship this Catholic icon seems a paradox. Legend has it that in 1531, in Teypac near Mexico City an apparition of the Blessed Mother appeared to a peasant, Juan Diego, urging him to ask the bishop to erect a church on that spot. Diego tried in vain to convince the bishop. Ultimately the Blessed Mother directed Diego to fill his cloak with flowers he would find at the top of the hill. Under a wintry frost he found beautiful red roses in bloom which he collected in his cloak and took to the bishop. When he opened his cloak the roses scattered to the ground revealing the image of the Virgin Mary imprinted on the rough cloth.

The image imprinted is said to have shown a striking resemblance to the original image of the Lady of Guadalupe found in Extremadura, Spain. The church was built and the cloak can still be seen on the site where thousands of her followers come to seek her blessings.

‘Pilgrims Carrying Icon of the Virgin Mary at the Basilica de Guadalupe, Mexico City’ © Rick Gerharter photo

Theories abound among historians that the icon syncretically represents both the Virgin Mary and the indigenous Mexican goddess Tonantzin. Others believe the pregnant Virgin in the image was a simplified and sanitized version of the Aztec mother goddess. This syncretism perhaps provided a way for the Spaniards to convert the indigenous early Mexicans to Christianity by allowing them to secretly practice their own religion. Her image was even carried into battle during the Mexican Revolution by the armies of Emiliano Zapata, and during the Mexican War of Independence by Miguel Hidalgo.

And if you look up to the night skies on December 12 you will supposedly see the constellations mirrored the stars on the lady of Guadalupe’s cloak. Whatever the origin of her image, even to a non-believer, she emanates a serene, benevolent aura. As the Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes said: “…one may no longer consider himself a Christian, but you cannot truly be considered a Mexican unless you believe in the Virgin of Guadalupe.”

Copy Right

All Rights Reserved ©Sukanya Rahman 2011

Categories